The System Traps of Applying to Medical School

By Matt Bass · September 10, 2023 ·EXPLANATION

When I read Thinking in Systems: A Primer by Donella Meadows, it had me thinking about systems in my life. In University, I was a pre-med student, so my pre-med friends and I spent a lot of time talking about the med school application process.

It’s no secret that applying to medical school is expensive. People spend many years and a lot of money (e.g. MCAT classes, essay editing services, prerequisite classes, application fees, travel expenses for interviews, medical masters degree, etc) in order to earn that acceptance.

Let’s look at the application process as a system using the tools Meadows provides in Thinking in Systems.

Tragedy of the Commons

Applications to med school are done via the AAMC, a one stop shop for filling out the necessary requirements then sending it off to multiple programs with a push of a button. Before electronic applications people would apply by mailing physical paper applications. The friction of applying limited people to apply either to local programs or big name institutions. This allowed smaller programs to cater to a more local population without competition from the wider applicant pool.

The ability to apply to any school across the country so easily has greatly increased the number of applicants per program. To increase the chances of being accepted applicants apply to as many programs as possible, most people I know applied to at least 20 programs. Some apply to as many as 40 programs, ringing up costs of more than $5,000 for application fees alone.

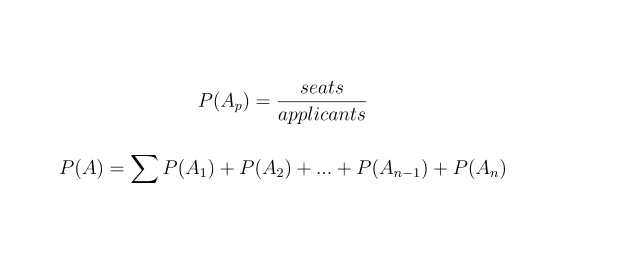

Let’s say the probability of acceptance for a given program is the number of seats divided by the number of applicants. This makes the assumption that everyone who applies is equally likely to get in, which is not true, but good enough for the point I am trying to make.

Applying to an additional program increases your chances of being accepted into any program. Yet by having more applicants per program, the probability of acceptance goes down for all applicants to a given program.

So we have a tragedy of the commons, people acting in individual interest harm the collective. Everyone wants to get in so everyone applies to as many programs as they can afford to. The more programs people apply to the less people who get accepted at each program.

Winner Takes All

If you are an adcom (admissions committee), your job is to select the best applicants of the people who have applied. Only the best applicants are the same group of people who apply to many schools. The best candidates are the ones who have the most resources for things like research, volunteer trips, and paying for med school application fees. So they are able to apply to the most programs.

You may think that the best applicants know they are the best, and therefore only apply to the best programs. This isn’t true, they know how competitive the process is and want to get into any program. Of course they could reject an interview once they receive an acceptance at a program they like. But the acceptances are sent out much later after the interviews are conducted. So candidates are incentivized to accept as many interviews as is financially feasible (travel expenses) in order to improve their odds.

Many programs have moved their interviews online since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Now there is even less friction to accepting every interview invite you receive.

The result is the most competitive applicants get all the interview slots leaving disproportionately fewer slots for the applicants in the middle of the distribution. Or in other words, the winner takes all. These winners will only go to one school, yet they will attend many interviews, limited only by how many programs they applied to. While the average candidate may receive no interview invites that cycle.

All Together Now

These two system traps work together to create a system where only a select subset of the applicants to a given program receive an invite to interview. The problem is that in the middle of the distribution are capable people who are willing and able to perform the task, but are not given the opportunity.

Universities claim to have a “holistic process” of selection yet quantifiable aspects such as GPA and MCAT scores are used to rank students, often acting as a first pass eliminating 40% of applicants. This is done to reduce the number of applications the adcom has to read. Some programs receive as many as 7 thousand applications a year and only around 5% can be invited for an interview. So some kind of triage is required as a first pass.

People may argue that it’s ok if only the most qualified candidates get an interview or acceptance letter. They might say that this is a feature and not a bug. I think it unnecessarily filters out quality candidates and unfairly rewards the affluent. For a system that claims to be a meroticracy, I think it is doing a lousy job at doing so. As for a more equitable system, I find using a lottery based on a ranking system to be an interesting direction.